Author's Note and Further Reading from The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi

The Indian Ocean is arguably among the oldest seas in maritime history, witness to over five thousand years of humans traveling its shores and traversing its expanse. Pilgrims and pirates, enslaved persons and royalty, traders and scholars. In our modern age, we are accustomed to thinking of continents and land borders, but rarely do we see the sea and its littoral as a place of shared culture. But long before the so-called European “Age of Exploration,” (an age that would do more damage to existing Indian Ocean networks and indigenous populations than any such incursion before), the ports of the Indian Ocean were bustling, cosmopolitan places where one could find goods and people from all over.

Its medieval history has fascinated me since I was an undergrad, first learning of the accounts of the famous Geniza merchants, members of a Jewish diaspora that stretched from North Africa to India. There was something so relatable and human about these often mundane accounts of normal people’s lives: people who weren’t sultans or generals, but parents purchasing gifts for their kid’s weddings, fretting about in-laws and business decisions, and mourning the sudden death of beloved siblings lost at sea—the sort of connections that make the past seem alive. It was always my dream to write a book set in this world, to pull on the stories that had resonated so deeply and when I first began, I was thrilled to finally have a proper work excuse to throw myself into research. Indeed, the phrase “I’m going to make it completely historically accurate except for the plot” came out of my mouth at least once.

Reader, I am fortunate that such a delusionally ambitious statement didn’t instantly summon my own Raksh. For as I have been reminded again and again and AGAIN, history is a construct, ever-changing and always subjective. Not only does it reveal the biases of its teller, audience, and intention, but also there is often much we simply don’t know. While the past decade has seen astonishing developments in the study of the medieval Indian Ocean world, I have no doubt that by the time this book is published, some detail I believed factually sound will be disproved.

I have endeavored to make it historically believable then, trying to balance scholarship with the spirit of the story. There are, of course, plenty of fantasist’s touches. Would Amina have realized Aden was balanced on top of a submerged extinct volcano? No, but it is a setting too fabulous to ignore. Is the Moon of Saba a true item? Absolutely not: one does not spend one’s time reading terrifying tales of djinns and demons and then give directions to summoning such a creature in a commercial novel. However nothing would delight me more than if you were intrigued enough by the history underlying Amina’s story to learn more about this world, and so I’m sharing some sources. This isn’t a comprehensive list—that would be a novella itself—but rather some enjoyable and accessible reads I think fellow history nerds would enjoy.

Let’s start with primary accounts (I’m listing English translations here; if you are an Arabic reader, you’ll have far better options). I’ve already mentioned the Geniza traders, and while a great number of books have been written about their lives, a good one is India Traders of the Middle Ages: Documents from the Cairo Geniza. Then there are the travelers. Ibn Battuta is the most famous, though slightly later; his lovely recollections of Mogadishu informed descriptions of that city in this book. Ibn Jubayr is more contemporaneous, and though his travels kept him slightly northward, he had a lot of opinions about maritime travel. Much closer to Amina’s world, is the traveling merchant and would-be geographer, Ibn al-Mujawir, whose very entertaining—if occasionally quite scandalous—trips to Aden, Socotra, and the southern Arabian coast were instrumental. From the perspective of actual seafarers are Abu Zayd al-Sirafi’s Accounts of India and China and The Book of the Wonders of India, a collection of sailors yarns credited to Buzurg ibn Shahriyar al-Ramhormuzi, a captain who was likely fictional.

If information on the lives of regular people during the medieval period is difficult to uncover, reliable accounts on the lives of criminals, those who often made a living by covering their tracks can be even more elusive. My favorite primary source is the 13th century trickster’s manual The Book of Charlatans by al-Jawbari, several of whose ruses made their way into this text. For criminal tales that skirt the line between fact and fiction, Robert Irwin’s The Arabian Nights: a companion offers some of the history behind the collections’s rogues, and C.E. Bosworth’s first volume in The Mediaeval Islamic Underworld translates and contextualizes several of the odes and legends about the Banu Sasan. Less whimsical but more telling is the actual criminal activity recorded and studied in works such as Carl F. Petry’s The Criminal Underworld in a Medieval Islamic Society and Hassan S. Khalilieh’s articles on piracy and Islamic law at sea. However to better understand the place of piracy in the medieval Indian Ocean, one must read far more widely. An entire book could be written just on the place of pirates in modern and historical lore. Both romanticized and villainized; they can be spun as heroic corsairs, justified freedom fighters, or murderous enslavers…it all depend on who’s telling their story. But in primary accounts and historical studies, much of what I read painted a picture of various groups of people who were often just as part and parcel of the littoral society they lived in as were traders and navies. Alongside Khalilieh’s articles, I found the work of scholars such as Roxani Eleni Margariti, Sebastian R. Prange, and Lakshmi Subramanian most illuminating.

To put together the lives of noncriminal citizens and the cities they dwelled in, I relied heavily on Margariti’s Aden and the Indian Ocean Trade, Elizabeth A. Lambourn’s Abraham’s Luggage, Yossef Rapoport’s Marriage, Money and Divorce in Medieval Islamic Society, and Delia Cortese and Simonetta Calderini’s Women and the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Chapurukha M. Kusimba’s The Rise and Fall of Swahili States was an excellent guide to the world from which Majed and Amina’s mother hailed, and on conflicts further abroad, I found Paul M. Cobb’s The Race for Paradise, Amin Maalouf’s The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, Loud and Metcalfe’s The Society of Norman Italy, and Hussein Fancy’s The Mercenary Mediterranean helpful in providing context for Falco’s character. For a primary source that offers a very different and personal take on Muslim and Christian interactions during the Crusades, I suggest The Book of Contemplation by Usama ibn Munqidh. For those who enjoy audio content, I highly recommend checking out the podcast series New Books in the Indian Ocean World and the Ottoman History Podcast.

Absolutely nothing bedeviled me like researching anything maritime-related. From ship details to sailing schedules to life at sea, what I could glean at first largely seemed to contradict other sources and while there’s a fair amount of information after the 14th century, maritime history in the early medieval and late classical eras is less well-known. I did find some gems, however. George F. Hourani’s Arab Seafaring is a classic in the genre, and Tim Severin’s account of the Sindbad voyage, in which a ninth century vessel was reconstructed and sailed from Oman to Singapore discusses technology that predates Amina’s Marawati but is still a delight. Most helpful (and far more recent) is the work of Dionisius A. Agius, in particular his book Classic Ships of Islam. This was also a subject I relied heavily on academic articles; the scholarship of Ranabir Chakravarti, Inês Bénard and Juan Acevedo being of note. Yossef Rapoport’s Islamic Maps is a gorgeously rendered volume that helped me better visualize and understand how Amina would have conceived of the geography of her world, and for a larger overview of the Indian Ocean in history, I recommend The Ocean of Churn: How the Indian Ocean Shaped Human History by Sanjeev Sanyal; Dhow Cultures of the Indian Ocean: cosmopolitanism, commerce and Islam by Abdul Sheriff; Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast by Sebastian Prange; and Oman: a maritime history by Abdulrahman Al-Salimi and Eric Staples.

It is difficult to overstate how prevalent what we now call magic was in the medieval world and how difficult as well to remove our own modern biases from understanding that. Astrological predictions were the law of the land, relied upon by scholars and sultans, and folk rituals were part of everyday life, no matter a person’s religious background. I won’t attempt a comprehensive list (especially with some of the most fascinating scholarship being done by young academics right now) but will instead share that I found Legends of the Fire Spirits by Robert Lebling and Islam, Arabs, and the Intelligent World of the Jinn by Amira El-Zein very helpful. For a different perspective, I recommend Michael Muhammad Knight’s Magic in Islam, and for those who enjoy podcasts, Ali A. Olomi is a treasure.

So much of this story is inspired by folktales that it’s difficult to know where to start in recommending them but I’ll begin with what I am asked most frequently: my current favorite edition of the 1001 Nights is the Annotated Arabian Nights. Yasmine Seale’s translation is beautiful, and the accompanying art and contextual information is not to be missed. Tales of the Marvelous and News of the Strange, as well as al-Qazwini’s Marvels of Creation are also highly entertaining. You can read English versions of the epic figures mentioned in this book with Melanie Magidow’s translation of Dhat al-Himma in The Tale of Princess Fatima, Warrior Woman; Lena Jayyusi’s The Adventures of Sayf Ben Dhi Yazan; and James E. Montgomery’s Diwan 'Antarah ibn Shaddad. For even more female fighters, you can check out Remke Kruk’s Warrior Women of Islam.

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the modern authors that started me on this journey: the incomparable Naguib Mahfouz, Radwa Ashour and Amitav Ghosh. Though I recommend all their books, for stories also inspired by the folktales and history mentioned here, I suggest you check out Arabian Nights and Days, Siraaj, and In an Antique Land.

Happy reading!

The Indian Ocean is arguably among the oldest seas in maritime history, witness to over five thousand years of humans traveling its shores and traversing its expanse. Pilgrims and pirates, enslaved persons and royalty, traders and scholars. In our modern age, we are accustomed to thinking of continents and land borders, but rarely do we see the sea and its littoral as a place of shared culture. But long before the so-called European “Age of Exploration,” (an age that would do more damage to existing Indian Ocean networks and indigenous populations than any such incursion before), the ports of the Indian Ocean were bustling, cosmopolitan places where one could find goods and people from all over.

Its medieval history has fascinated me since I was an undergrad, first learning of the accounts of the famous Geniza merchants, members of a Jewish diaspora that stretched from North Africa to India. There was something so relatable and human about these often mundane accounts of normal people’s lives: people who weren’t sultans or generals, but parents purchasing gifts for their kid’s weddings, fretting about in-laws and business decisions, and mourning the sudden death of beloved siblings lost at sea—the sort of connections that make the past seem alive. It was always my dream to write a book set in this world, to pull on the stories that had resonated so deeply and when I first began, I was thrilled to finally have a proper work excuse to throw myself into research. Indeed, the phrase “I’m going to make it completely historically accurate except for the plot” came out of my mouth at least once.

Reader, I am fortunate that such a delusionally ambitious statement didn’t instantly summon my own Raksh. For as I have been reminded again and again and AGAIN, history is a construct, ever-changing and always subjective. Not only does it reveal the biases of its teller, audience, and intention, but also there is often much we simply don’t know. While the past decade has seen astonishing developments in the study of the medieval Indian Ocean world, I have no doubt that by the time this book is published, some detail I believed factually sound will be disproved.

I have endeavored to make it historically believable then, trying to balance scholarship with the spirit of the story. There are, of course, plenty of fantasist’s touches. Would Amina have realized Aden was balanced on top of a submerged extinct volcano? No, but it is a setting too fabulous to ignore. Is the Moon of Saba a true item? Absolutely not: one does not spend one’s time reading terrifying tales of djinns and demons and then give directions to summoning such a creature in a commercial novel. However nothing would delight me more than if you were intrigued enough by the history underlying Amina’s story to learn more about this world, and so I’m sharing some sources. This isn’t a comprehensive list—that would be a novella itself—but rather some enjoyable and accessible reads I think fellow history nerds would enjoy.

Let’s start with primary accounts (I’m listing English translations here; if you are an Arabic reader, you’ll have far better options). I’ve already mentioned the Geniza traders, and while a great number of books have been written about their lives, a good one is India Traders of the Middle Ages: Documents from the Cairo Geniza. Then there are the travelers. Ibn Battuta is the most famous, though slightly later; his lovely recollections of Mogadishu informed descriptions of that city in this book. Ibn Jubayr is more contemporaneous, and though his travels kept him slightly northward, he had a lot of opinions about maritime travel. Much closer to Amina’s world, is the traveling merchant and would-be geographer, Ibn al-Mujawir, whose very entertaining—if occasionally quite scandalous—trips to Aden, Socotra, and the southern Arabian coast were instrumental. From the perspective of actual seafarers are Abu Zayd al-Sirafi’s Accounts of India and China and The Book of the Wonders of India, a collection of sailors yarns credited to Buzurg ibn Shahriyar al-Ramhormuzi, a captain who was likely fictional.

If information on the lives of regular people during the medieval period is difficult to uncover, reliable accounts on the lives of criminals, those who often made a living by covering their tracks can be even more elusive. My favorite primary source is the 13th century trickster’s manual The Book of Charlatans by al-Jawbari, several of whose ruses made their way into this text. For criminal tales that skirt the line between fact and fiction, Robert Irwin’s The Arabian Nights: a companion offers some of the history behind the collections’s rogues, and C.E. Bosworth’s first volume in The Mediaeval Islamic Underworld translates and contextualizes several of the odes and legends about the Banu Sasan. Less whimsical but more telling is the actual criminal activity recorded and studied in works such as Carl F. Petry’s The Criminal Underworld in a Medieval Islamic Society and Hassan S. Khalilieh’s articles on piracy and Islamic law at sea. However to better understand the place of piracy in the medieval Indian Ocean, one must read far more widely. An entire book could be written just on the place of pirates in modern and historical lore. Both romanticized and villainized; they can be spun as heroic corsairs, justified freedom fighters, or murderous enslavers…it all depend on who’s telling their story. But in primary accounts and historical studies, much of what I read painted a picture of various groups of people who were often just as part and parcel of the littoral society they lived in as were traders and navies. Alongside Khalilieh’s articles, I found the work of scholars such as Roxani Eleni Margariti, Sebastian R. Prange, and Lakshmi Subramanian most illuminating.

To put together the lives of noncriminal citizens and the cities they dwelled in, I relied heavily on Margariti’s Aden and the Indian Ocean Trade, Elizabeth A. Lambourn’s Abraham’s Luggage, Yossef Rapoport’s Marriage, Money and Divorce in Medieval Islamic Society, and Delia Cortese and Simonetta Calderini’s Women and the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Chapurukha M. Kusimba’s The Rise and Fall of Swahili States was an excellent guide to the world from which Majed and Amina’s mother hailed, and on conflicts further abroad, I found Paul M. Cobb’s The Race for Paradise, Amin Maalouf’s The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, Loud and Metcalfe’s The Society of Norman Italy, and Hussein Fancy’s The Mercenary Mediterranean helpful in providing context for Falco’s character. For a primary source that offers a very different and personal take on Muslim and Christian interactions during the Crusades, I suggest The Book of Contemplation by Usama ibn Munqidh. For those who enjoy audio content, I highly recommend checking out the podcast series New Books in the Indian Ocean World and the Ottoman History Podcast.

Absolutely nothing bedeviled me like researching anything maritime-related. From ship details to sailing schedules to life at sea, what I could glean at first largely seemed to contradict other sources and while there’s a fair amount of information after the 14th century, maritime history in the early medieval and late classical eras is less well-known. I did find some gems, however. George F. Hourani’s Arab Seafaring is a classic in the genre, and Tim Severin’s account of the Sindbad voyage, in which a ninth century vessel was reconstructed and sailed from Oman to Singapore discusses technology that predates Amina’s Marawati but is still a delight. Most helpful (and far more recent) is the work of Dionisius A. Agius, in particular his book Classic Ships of Islam. This was also a subject I relied heavily on academic articles; the scholarship of Ranabir Chakravarti, Inês Bénard and Juan Acevedo being of note. Yossef Rapoport’s Islamic Maps is a gorgeously rendered volume that helped me better visualize and understand how Amina would have conceived of the geography of her world, and for a larger overview of the Indian Ocean in history, I recommend The Ocean of Churn: How the Indian Ocean Shaped Human History by Sanjeev Sanyal; Dhow Cultures of the Indian Ocean: cosmopolitanism, commerce and Islam by Abdul Sheriff; Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast by Sebastian Prange; and Oman: a maritime history by Abdulrahman Al-Salimi and Eric Staples.

It is difficult to overstate how prevalent what we now call magic was in the medieval world and how difficult as well to remove our own modern biases from understanding that. Astrological predictions were the law of the land, relied upon by scholars and sultans, and folk rituals were part of everyday life, no matter a person’s religious background. I won’t attempt a comprehensive list (especially with some of the most fascinating scholarship being done by young academics right now) but will instead share that I found Legends of the Fire Spirits by Robert Lebling and Islam, Arabs, and the Intelligent World of the Jinn by Amira El-Zein very helpful. For a different perspective, I recommend Michael Muhammad Knight’s Magic in Islam, and for those who enjoy podcasts, Ali A. Olomi is a treasure.

So much of this story is inspired by folktales that it’s difficult to know where to start in recommending them but I’ll begin with what I am asked most frequently: my current favorite edition of the 1001 Nights is the Annotated Arabian Nights. Yasmine Seale’s translation is beautiful, and the accompanying art and contextual information is not to be missed. Tales of the Marvelous and News of the Strange, as well as al-Qazwini’s Marvels of Creation are also highly entertaining. You can read English versions of the epic figures mentioned in this book with Melanie Magidow’s translation of Dhat al-Himma in The Tale of Princess Fatima, Warrior Woman; Lena Jayyusi’s The Adventures of Sayf Ben Dhi Yazan; and James E. Montgomery’s Diwan 'Antarah ibn Shaddad. For even more female fighters, you can check out Remke Kruk’s Warrior Women of Islam.

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the modern authors that started me on this journey: the incomparable Naguib Mahfouz, Radwa Ashour and Amitav Ghosh. Though I recommend all their books, for stories also inspired by the folktales and history mentioned here, I suggest you check out Arabian Nights and Days, Siraaj, and In an Antique Land.

Happy reading!

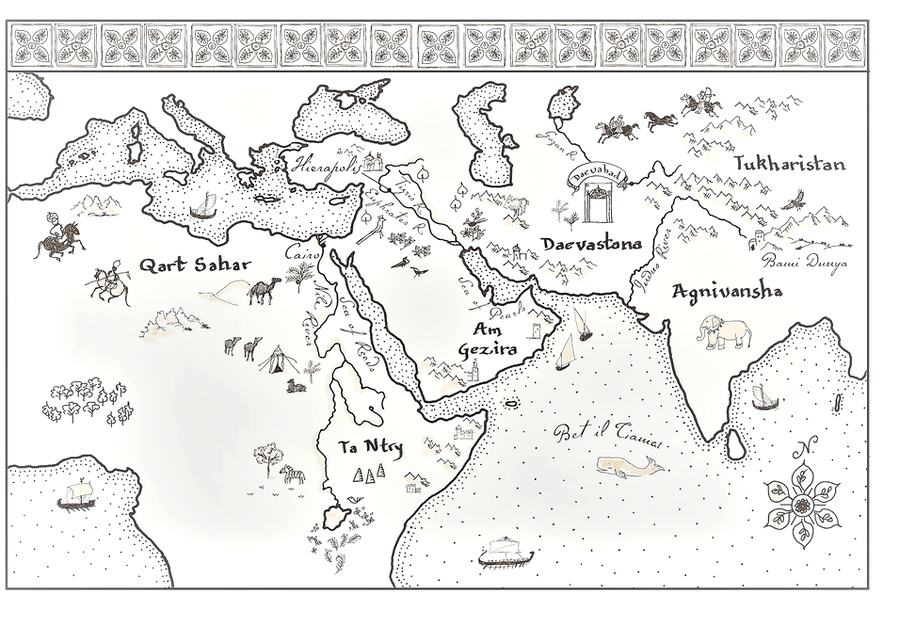

The World of The Daevabad Trilogy

Whether you're an audio book listener looking for the glossary or a reader wanting to catch up, here you'll find a guide to the world behind The Daevabad Trilogy. (Warning: there are some very small spoilers for The City of Brass in the character list!)

The Six Tribes of the Djinn

"I told you before that Suleiman was a clever man. Before his curse, all daevas were the same. We looked similar, spoke a single language, practiced identical rites. When Suleiman freed us, he scattered us across the world he knew, changing our tongues and appearances."

"I told you before that Suleiman was a clever man. Before his curse, all daevas were the same. We looked similar, spoke a single language, practiced identical rites. When Suleiman freed us, he scattered us across the world he knew, changing our tongues and appearances."

|

Sprawling from the shores of the Maghreb across the vast depths of the Sahara Desert is QART SAHAR— a land of fables and adventure even to the djinn. An enterprising people not particularly enamored of being ruled by foreigners, the Sahrayn know the mysteries of their country better than any— the still lush rivers that flow in caves deep below the sand dunes and the ancient citadels of human civilizations lost to time and touched by forgotten magic. Skilled sailors, the Sahrayn travel upon ships of conjured smoke and sewn cord over sand and sea alike. |

|

Nestled between the rushing headwaters of the Nile River and the salty coast of Bet il Tiamat lies TA NTRY, the fabled homeland of the mighty Ayaanle tribe. Rich in gold and salt— and far enough from Daevabad that its deadly politics are more game than risk, the Ayaanle are a people to envy. But behind their gleaming coral mansions and sophisticated salons lurks a history they’ve begun to forget . . . one that binds them in blood to their Geziri neighbors. |

|

Surrounded by water and caught behind the thick band of humanity in the Fertile Crescent, the djinn of AM GEZIRA awoke from Suleiman’s curse to a far different world than their fire- blooded cousins. Retreating to the depths of the Empty Quarter, to the dying cities of the Nabateans and to the forbidding mountains of southern Arabia, the Geziri eventually learned to share the hardships of the land with their human neighbors, becoming fierce protectors of the shafit in the process. From this country of wandering poets and zulfiqar- wielding warriors came Zaydi al Qahtani, the rebel- turned- king who would seize Daevabad and Suleiman’s seal from the Nahid family in a war that remade the magical world.

|

|

Stretching from the Sea of Pearls across the plains of Persia and the mountains of gold- rich Bactria is mighty DAEVASTANA— and just past its Gozan River lies Daevabad, the hidden city of brass. The ancient seat of the Nahid Council— the famed family of healers who once ruled the magical world— Daevastana is a coveted land, its civilization drawn from the ancient cities of Ur and Susa and the nomadic horsemen of the Saka. A proud people, the Daevas claimed the original name of the djinn race as their own . . . a slight that the other tribes never forget. |

|

East of Daevabad, twisting through the peaks of Karakorum Mountains and the vast sands of the Gobi is TUKHARISTAN. Trade is its lifeblood, and in the ruins of forgotten Silk Road kingdoms, the Tukharistanis make their homes. They travel unseen in caravans of smoke and silk along corridors marked by humans millennia ago, carrying with them things of myth: golden apples that cure any disease, jade keys that open worlds unseen, and perfumes that smell of paradise. |

|

Extending from the brick bones of old Harappa through the rich plains of the Deccan and misty marshes of the Sundarbans lies AGNIVANSHA. Blessedly lush in every resource that could be dreamed— and separated from their far more volatile neighbors by wide rivers and soaring mountains— Agnivansha is a peaceful land famed for its artisans and jewels . . . and its savvy in staying out of Daevabad’s tumultuous politics. |

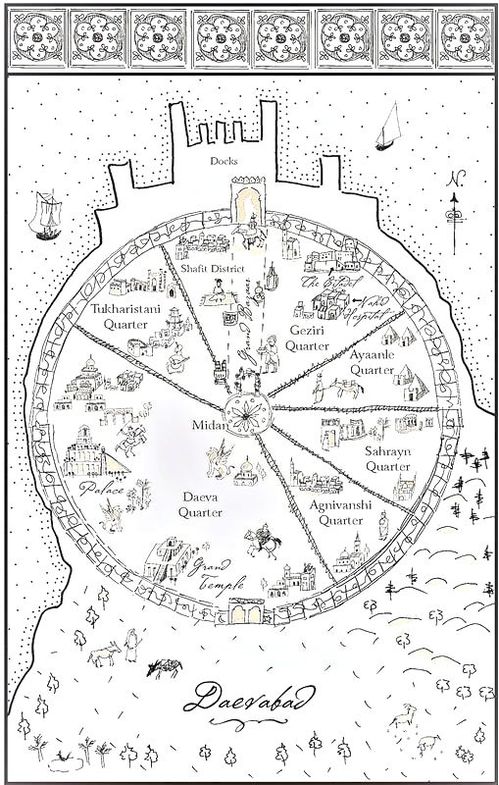

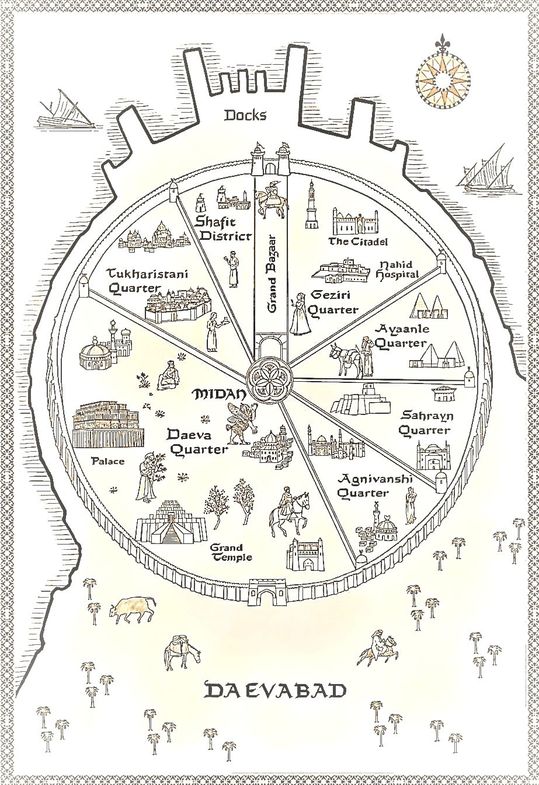

Daevabad

"Our ancestors spun a city out of magic—pure Daeva magic—to create a wonder unlike the world had ever seen. We pulled an island out of the depths of a marid-haunted lake and filled it with libraries and pleasure gardens. Winged lions flew over its skies and in its streets, our women and children walked in absolute safety."

"Our ancestors spun a city out of magic—pure Daeva magic—to create a wonder unlike the world had ever seen. We pulled an island out of the depths of a marid-haunted lake and filled it with libraries and pleasure gardens. Winged lions flew over its skies and in its streets, our women and children walked in absolute safety."

Cast of Characters

THE ROYAL FAMILY

Daevabad is currently ruled by the Qahtani family, descendants of ZAYDI AL QAHTANI, the Geziri warrior who led a rebellion to overthrow the NAHID COUNCIL and establish equality for the shafit centuries ago

GHASSAN AL QAHTANI, King of the magical realm, defender of the faith

MUNTADHIR, Ghassan’s eldest son from his Geziri first wife, the king’s designated successor

HATSET, Ghassan’s Ayaanle second wife and queen, hailing from a powerful family in Ta Ntry

ZAYNAB, Ghassan and Hatset’s daughter, princess of Daevabad

ALIZAYD, the king’s youngest son, given to the Citadel as a child to be trained as Muntadhir's future Qaid

Their Court and Royal Guard

WAJED, Qaid and leader of the djinn army

ABU NUWAS, a Geziri officer

KAVEH E-PRAMUKH, the Daeva Grand Wazir

JAMSHID, his son and close confidant of Emir Muntadhir

ABUL DAWANIK, a trade envoy from Ta Ntry

ABU SAYF, an old soldier and scout in the Royal Guard

AQISA and LUBAYD: warriors and trackers from Bir Nabat, a village in Am Gezira

THE MOST HIGH AND BLESSED NAHIDS

The original rulers of Daevabad and descendants of Anahid, the Nahids were a family of extraordinary magical healers, hailing from the Daeva tribe.

ANAHID, Suleiman’s chosen and the original founder of Daevabad

RUSTAM, one of the last Nahid healers and a skilled botanist, murdered by the ifrit

MANIZHEH, Rustam’s sister and one of the most powerful Nahid healers in centuries, murdered by the ifrit

NAHRI, her daughter of uncertain parentage, left abandoned as a young child in the human land of Egypt

Their Supporters

DARAYAVAHOUSH, the last descendent of the Afshins, a Daeva military caste family which served at the right hand of the Nahid Council, known as the Scourge of Qui-zi for his violent acts during the war and later revolt against Zaydi al Qahtani

KARTIR, a Daeva high priest

NISREEN, Manizheh and Rustam’s former assistant and Nahri’s mentor

IRTEMIZ, MARDONIYE and BAHRAM, soldiers

THE SHAFIT

People of mixed human and djinn heritage forced to live in Daevabad, their rights sharply curtailed

SHEIKH ANAS, former leader of the Tanzeem and Ali’s mentor, executed by the king for treason

SISTER FATUMAI, Tanzeem leader who oversaw the group’s orphanage and charitable services

SUBHASHINI AND PARIMAL SEN, shafit physicians

THE IFRIT

Daevas who refused to submit to Suleiman thousands of years ago and were subsequently cursed, the mortal enemies of the Nahids

AESHMA, their leader

VIZARESH, the ifrit who first came for Nahri in Cairo

QANDISHA, the ifrit who enslaved and murdered Dara

THE FREED SLAVES OF THE IFRIT

Reviled and persecuted after Dara’s rampage, only three formerly enslaved djinn remain in Daevabad, freed and resurrected by Nahid healers years ago.

RAZU, a gambler from Tukharistan

ELASHIA, an artist from Qart Sahar

ISSA, a scholar and historian from Ta Ntry

Daevabad is currently ruled by the Qahtani family, descendants of ZAYDI AL QAHTANI, the Geziri warrior who led a rebellion to overthrow the NAHID COUNCIL and establish equality for the shafit centuries ago

GHASSAN AL QAHTANI, King of the magical realm, defender of the faith

MUNTADHIR, Ghassan’s eldest son from his Geziri first wife, the king’s designated successor

HATSET, Ghassan’s Ayaanle second wife and queen, hailing from a powerful family in Ta Ntry

ZAYNAB, Ghassan and Hatset’s daughter, princess of Daevabad

ALIZAYD, the king’s youngest son, given to the Citadel as a child to be trained as Muntadhir's future Qaid

Their Court and Royal Guard

WAJED, Qaid and leader of the djinn army

ABU NUWAS, a Geziri officer

KAVEH E-PRAMUKH, the Daeva Grand Wazir

JAMSHID, his son and close confidant of Emir Muntadhir

ABUL DAWANIK, a trade envoy from Ta Ntry

ABU SAYF, an old soldier and scout in the Royal Guard

AQISA and LUBAYD: warriors and trackers from Bir Nabat, a village in Am Gezira

THE MOST HIGH AND BLESSED NAHIDS

The original rulers of Daevabad and descendants of Anahid, the Nahids were a family of extraordinary magical healers, hailing from the Daeva tribe.

ANAHID, Suleiman’s chosen and the original founder of Daevabad

RUSTAM, one of the last Nahid healers and a skilled botanist, murdered by the ifrit

MANIZHEH, Rustam’s sister and one of the most powerful Nahid healers in centuries, murdered by the ifrit

NAHRI, her daughter of uncertain parentage, left abandoned as a young child in the human land of Egypt

Their Supporters

DARAYAVAHOUSH, the last descendent of the Afshins, a Daeva military caste family which served at the right hand of the Nahid Council, known as the Scourge of Qui-zi for his violent acts during the war and later revolt against Zaydi al Qahtani

KARTIR, a Daeva high priest

NISREEN, Manizheh and Rustam’s former assistant and Nahri’s mentor

IRTEMIZ, MARDONIYE and BAHRAM, soldiers

THE SHAFIT

People of mixed human and djinn heritage forced to live in Daevabad, their rights sharply curtailed

SHEIKH ANAS, former leader of the Tanzeem and Ali’s mentor, executed by the king for treason

SISTER FATUMAI, Tanzeem leader who oversaw the group’s orphanage and charitable services

SUBHASHINI AND PARIMAL SEN, shafit physicians

THE IFRIT

Daevas who refused to submit to Suleiman thousands of years ago and were subsequently cursed, the mortal enemies of the Nahids

AESHMA, their leader

VIZARESH, the ifrit who first came for Nahri in Cairo

QANDISHA, the ifrit who enslaved and murdered Dara

THE FREED SLAVES OF THE IFRIT

Reviled and persecuted after Dara’s rampage, only three formerly enslaved djinn remain in Daevabad, freed and resurrected by Nahid healers years ago.

RAZU, a gambler from Tukharistan

ELASHIA, an artist from Qart Sahar

ISSA, a scholar and historian from Ta Ntry

Glossary

Beings of Fire

DAEVA: The ancient term for all fire elementals before the djinn rebellion, as well as the name of the tribe residing in Daevastana, of which Dara and Nahri are both part. Once shapeshifters who lived for millennia, daevas had their magical abilities sharply curbed by the Prophet Suleiman as a punishment for harming humanity.

DJINN: A human word for “daeva.” After Zaydi al Qahtani’s rebellion, all his followers, and eventually all daevas, began using this term for their race.

IFRIT: The original daevas who defied Suleiman and were stripped of their abilities. Sworn enemies of the Nahid family, the ifrit revenge themselves by enslaving other djinn to cause chaos among humanity.

SIMURGH: Scaled firebirds that the djinn are fond of racing.

ZAHHAK: A large, flying, fire- breathing lizard- like beast.

Beings of Water

MARID: Extremely powerful water elementals. Near mythical to the djinn, the marid haven’t been seen in centuries, though it’s rumored the lake surrounding Daevabad was once theirs.

Beings of Air

PERI: Air elementals. More powerful than the djinn— and far more secretive— the peri keep resolutely to themselves.

RUKH: Enormous predatory firebirds that the peri can use for hunting.

SHEDU: Mythical winged lions, an emblem of the Nahid family.

Beings of Earth

GHOULS: The reanimated, cannibalistic corpses of humans who have made deals with the ifrit.

ISHTAS: A small, scaled creature obsessed with organization and footwear.

KARKADANN: A magical beast similar to an enormous rhinoceros with a horn as long as a man.

NASNAS: a venomous creature resembling a bisected human who prowls the deserts of Am Gezira and whose bite causes flesh to wither away.

Languages

DIVASTI: The language of the Daeva tribe.

DJINNISTANI: Daevabad’s common tongue, a merchant creole the djinn and shafit use to speak to those outside their tribe.

GEZIRIYYA: The language of the Geziri tribe, which only members of their tribe can speak and understand.

General Terminology

ABAYA: A loose, floor- length, full- sleeved dress worn by women.

ADHAN: The Islamic call to prayer.

AFSHIN: The name of the Daeva warrior family who once served the Nahid Council. Also used as a title.

AKHI: “my brother."

BAGA NAHID: The proper title for male healers of the Nahid family.

BANU NAHIDA: The proper title for female healers of the Nahid family.

CHADOR: An open cloak made from a semicircular cut of fabric, draped over the head and worn by Daeva women.

DIRHAM/DINAR: A type of currency used in Egypt.

DISHDASHA: A floor- length man’s tunic, popular among the Geziri.

EMIR: The crown prince and designated heir to the Qahtani throne.

FAJR: The dawn hour/dawn prayer.

GALABIYYA: A traditional Egyptian garment, essentially a floor- length tunic.

GHUTRA: a male headdress.

HAMMAM: A bathhouse.

ISHA: The late evening hour/evening prayer.

MAGHRIB: The sunset hour/sunset prayer.

MIDAN: A plaza/city square.

MIHRAB: A wall niche indicating the direction of prayer.

MUHTASIB: A market inspector.

NAVASATEM: a holiday held once a century to celebrate another generation of freedom from Suleiman’s servitude. Originally a Daeva festival, Navasatem is a beloved tradition in Daevabad, attracting djinn from all over the world to take part in weeks of festivals, parades and competitions.

QAID: The head of the Royal Guard, essentially the top military official in the djinn army.

RAKAT: A unit of prayer.

SHAFIT: People with mixed djinn and human blood.

SHAYLA a type of women’s headscarf

SHEIKH: A religious educator/leader.

SULEIMAN’S SEAL: The seal ring Suleiman once used to control the djinn, given to the Nahids and later stolen by the Qahtanis. The bearer of Suleiman’s ring can nullify any magic.

TALWAR: An Agnivanshi sword.

TANZEEM: A grassroots fundamentalist group in Daevabad dedicated to fighting for shafit rights and religious reform.

UKHTI: “my sister."

ULEMA: A legal body of religious scholars.

WAZIR: A government minister. ZAR: A traditional ceremony meant to deal with djinn possession.

ZUHR: The noon hour/noon prayer.

ZULFIQAR: The forked copper blades of the Geziri tribe; when inflamed, their poisonous edges destroy even Nahid flesh, making them among the deadliest weapons in this world.

DAEVA: The ancient term for all fire elementals before the djinn rebellion, as well as the name of the tribe residing in Daevastana, of which Dara and Nahri are both part. Once shapeshifters who lived for millennia, daevas had their magical abilities sharply curbed by the Prophet Suleiman as a punishment for harming humanity.

DJINN: A human word for “daeva.” After Zaydi al Qahtani’s rebellion, all his followers, and eventually all daevas, began using this term for their race.

IFRIT: The original daevas who defied Suleiman and were stripped of their abilities. Sworn enemies of the Nahid family, the ifrit revenge themselves by enslaving other djinn to cause chaos among humanity.

SIMURGH: Scaled firebirds that the djinn are fond of racing.

ZAHHAK: A large, flying, fire- breathing lizard- like beast.

Beings of Water

MARID: Extremely powerful water elementals. Near mythical to the djinn, the marid haven’t been seen in centuries, though it’s rumored the lake surrounding Daevabad was once theirs.

Beings of Air

PERI: Air elementals. More powerful than the djinn— and far more secretive— the peri keep resolutely to themselves.

RUKH: Enormous predatory firebirds that the peri can use for hunting.

SHEDU: Mythical winged lions, an emblem of the Nahid family.

Beings of Earth

GHOULS: The reanimated, cannibalistic corpses of humans who have made deals with the ifrit.

ISHTAS: A small, scaled creature obsessed with organization and footwear.

KARKADANN: A magical beast similar to an enormous rhinoceros with a horn as long as a man.

NASNAS: a venomous creature resembling a bisected human who prowls the deserts of Am Gezira and whose bite causes flesh to wither away.

Languages

DIVASTI: The language of the Daeva tribe.

DJINNISTANI: Daevabad’s common tongue, a merchant creole the djinn and shafit use to speak to those outside their tribe.

GEZIRIYYA: The language of the Geziri tribe, which only members of their tribe can speak and understand.

General Terminology

ABAYA: A loose, floor- length, full- sleeved dress worn by women.

ADHAN: The Islamic call to prayer.

AFSHIN: The name of the Daeva warrior family who once served the Nahid Council. Also used as a title.

AKHI: “my brother."

BAGA NAHID: The proper title for male healers of the Nahid family.

BANU NAHIDA: The proper title for female healers of the Nahid family.

CHADOR: An open cloak made from a semicircular cut of fabric, draped over the head and worn by Daeva women.

DIRHAM/DINAR: A type of currency used in Egypt.

DISHDASHA: A floor- length man’s tunic, popular among the Geziri.

EMIR: The crown prince and designated heir to the Qahtani throne.

FAJR: The dawn hour/dawn prayer.

GALABIYYA: A traditional Egyptian garment, essentially a floor- length tunic.

GHUTRA: a male headdress.

HAMMAM: A bathhouse.

ISHA: The late evening hour/evening prayer.

MAGHRIB: The sunset hour/sunset prayer.

MIDAN: A plaza/city square.

MIHRAB: A wall niche indicating the direction of prayer.

MUHTASIB: A market inspector.

NAVASATEM: a holiday held once a century to celebrate another generation of freedom from Suleiman’s servitude. Originally a Daeva festival, Navasatem is a beloved tradition in Daevabad, attracting djinn from all over the world to take part in weeks of festivals, parades and competitions.

QAID: The head of the Royal Guard, essentially the top military official in the djinn army.

RAKAT: A unit of prayer.

SHAFIT: People with mixed djinn and human blood.

SHAYLA a type of women’s headscarf

SHEIKH: A religious educator/leader.

SULEIMAN’S SEAL: The seal ring Suleiman once used to control the djinn, given to the Nahids and later stolen by the Qahtanis. The bearer of Suleiman’s ring can nullify any magic.

TALWAR: An Agnivanshi sword.

TANZEEM: A grassroots fundamentalist group in Daevabad dedicated to fighting for shafit rights and religious reform.

UKHTI: “my sister."

ULEMA: A legal body of religious scholars.

WAZIR: A government minister. ZAR: A traditional ceremony meant to deal with djinn possession.

ZUHR: The noon hour/noon prayer.

ZULFIQAR: The forked copper blades of the Geziri tribe; when inflamed, their poisonous edges destroy even Nahid flesh, making them among the deadliest weapons in this world.

*Map designed by Virginia Norey